Rocky Mountain Fungi Comic, Healing Earth, and Healing Ourselves

Mushrooms teach us about interdependence, a reciprocal relation between two seemingly interdependent bodies, ours and theirs.

Hey, what's up Mycobuds! I hope this finds you well.

Mushrooms and fungi are touching every aspect of our society from politics to science to pop culture to the environment. The more I learn about fungi, the deeper and more connected my life becomes.

This is a newsletter about fungi cultivating us as humans, as much as we cultivate fungi. Each newsletter features stories about mycologists, mushrooms in the news, and a personal writing and/or graphic novel panels from me!

If you like this newsletter share it with a myco-friend or subscribe! You can also find my upcoming Nerv podcast on Spotify, YouTube, and iTunes!

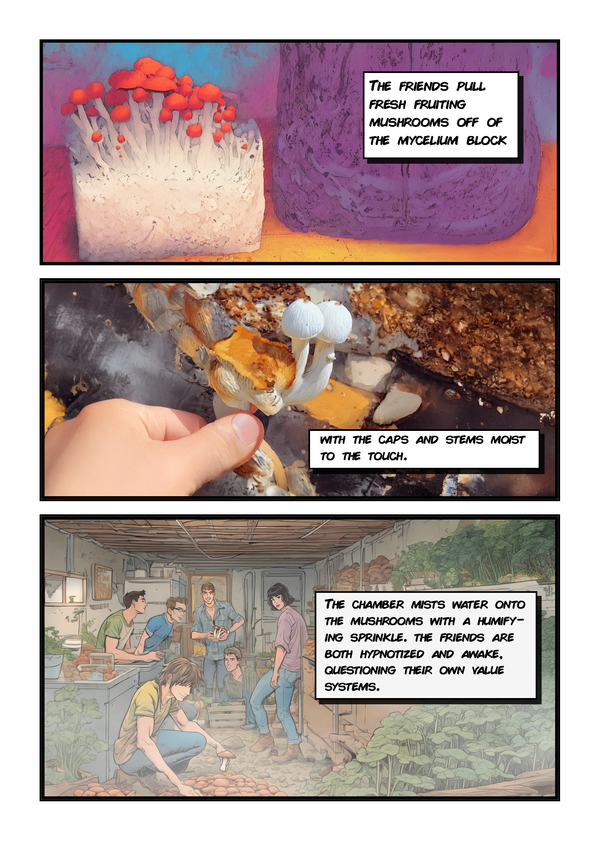

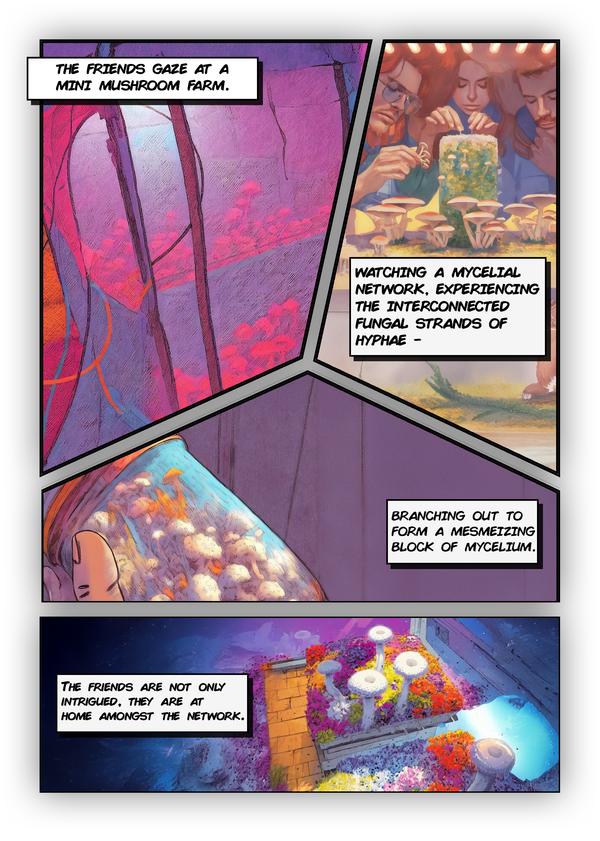

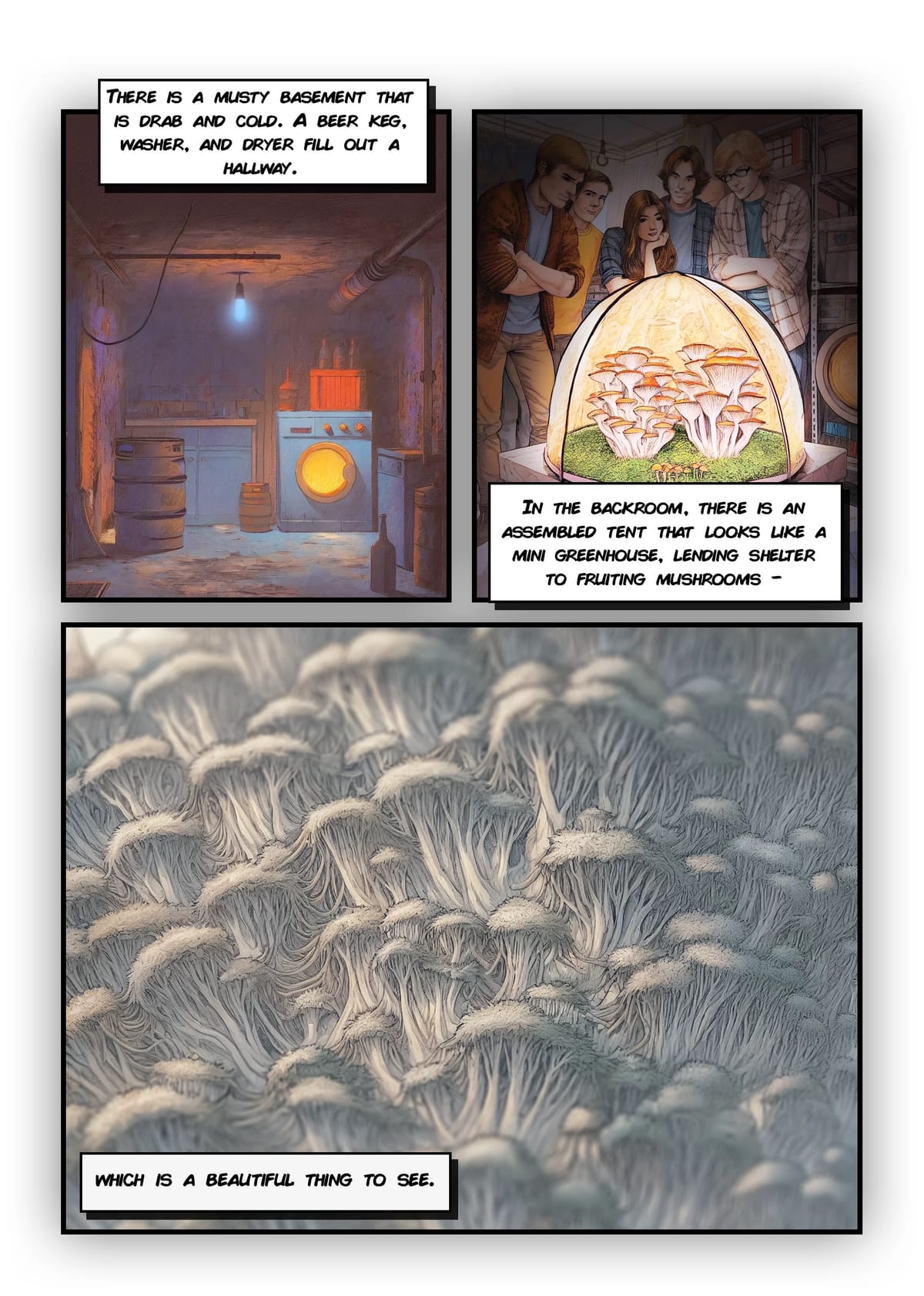

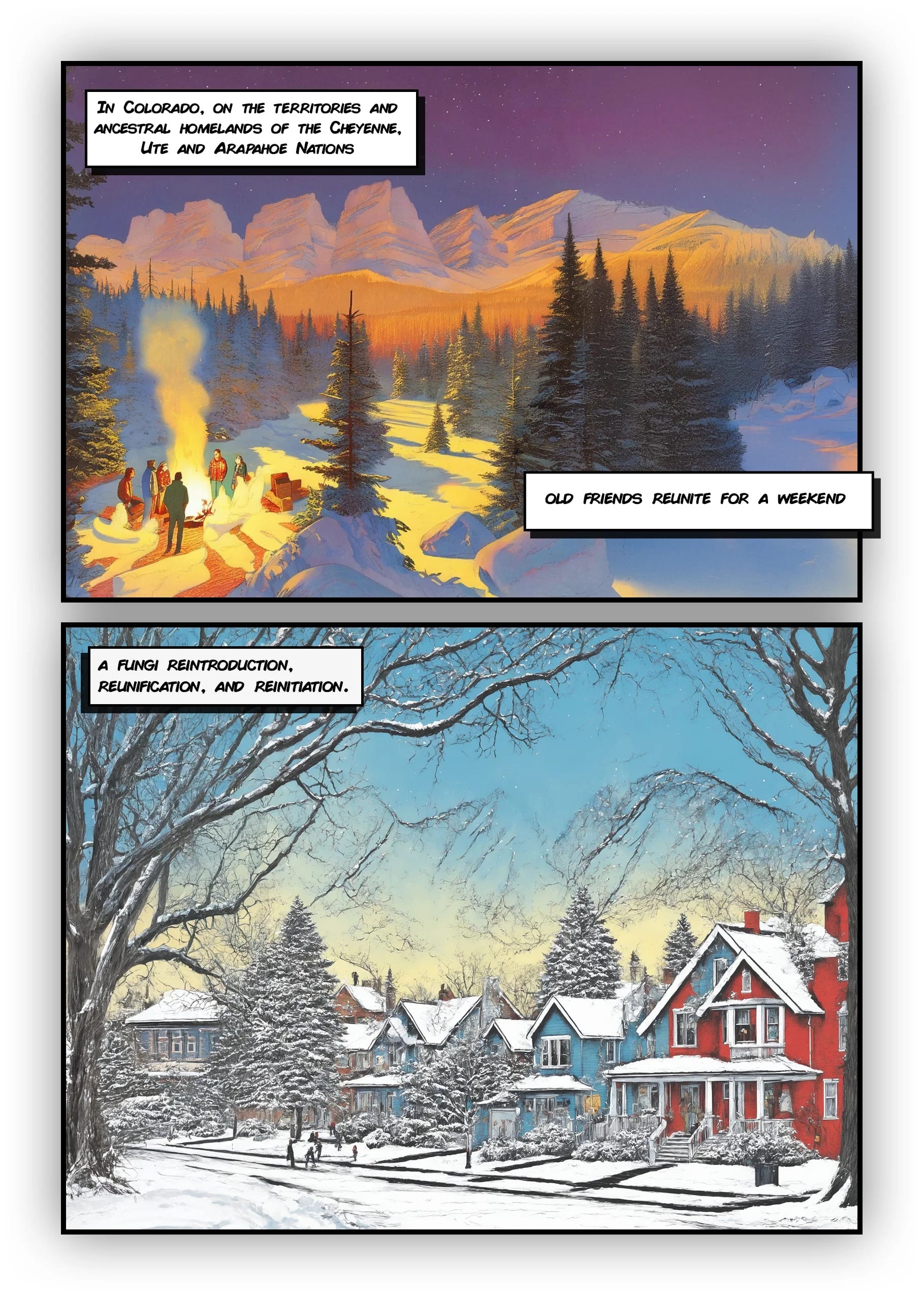

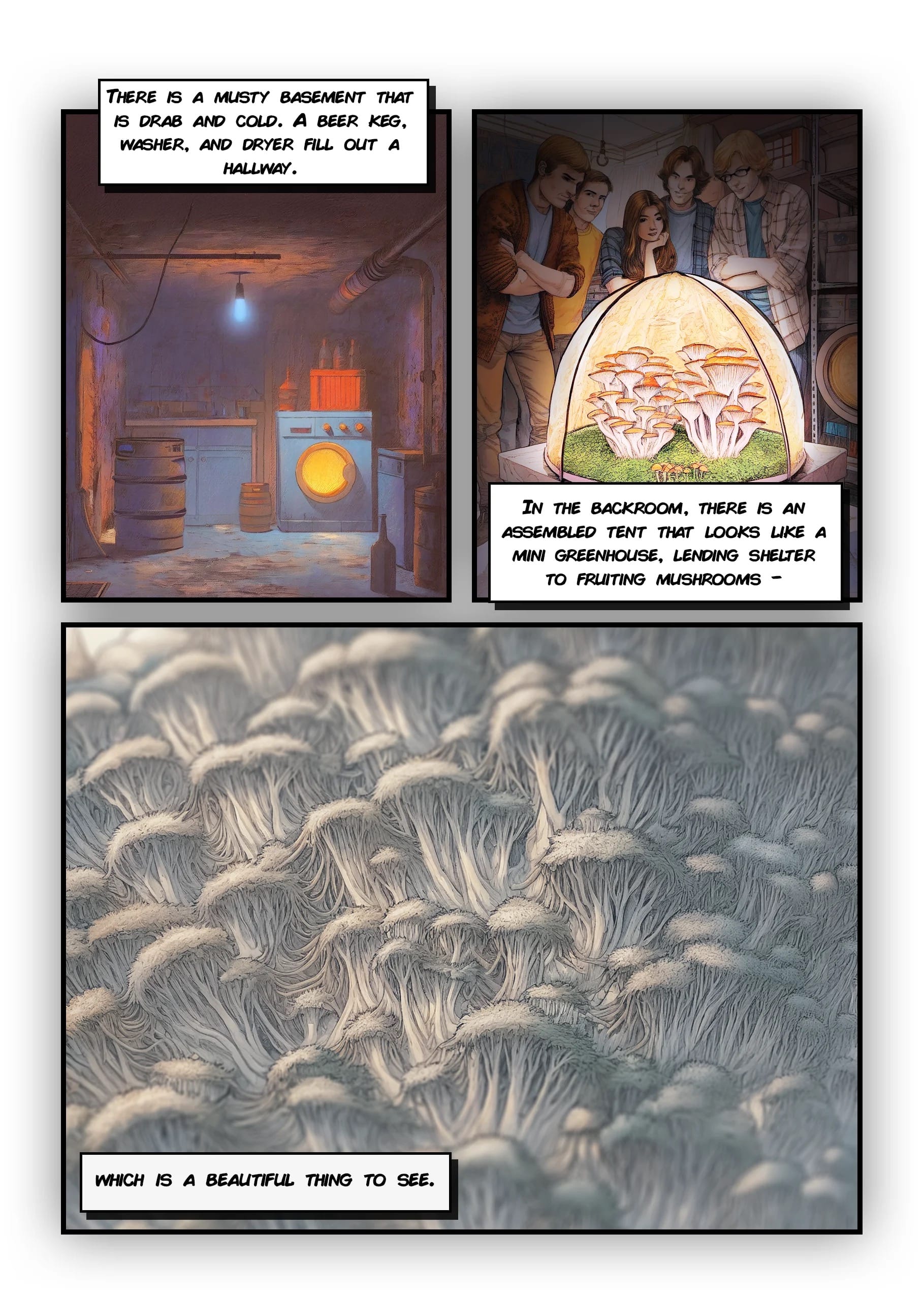

New Breathworker Graphic Novel Panels

I am working on a new graphic novel story: Rocky Mountain Fungi. It's a follow-up to Parking Lot Fungi, that I published a few months ago.

My next book is on how fungi have saved my life.

Mushrooms are my more-than-human friends—they are a guide from nature. I have faith that when things are difficult with human beings, my mycelial network friends will help soothe my soul.

Fungi have taught me that we are all interconnected.

Mushrooms teach us about interdependence, a reciprocal relation between two seemingly interdependent bodies, ours and theirs. In Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass, she shows the natural world—which includes human beings—as a living network of reciprocity, of constant giving and receiving. She highlights that there is a set of responsibilities with the land, and exchanging of energy.

She so aptly states:

“Action on behalf of life transforms. Because the relationship between self and the world is reciprocal, it is not a question of first getting enlightened or saved and then acting. As we work to heal the earth, the earth heals us.”

I finished a draft of my manuscript this summer. Below is a completed chapter from my book, that I'm excited to share.

How Marching for Black Lives Matter Helped Me Address My Racism (Part 1)

I am walking on Spring Street in downtown Los Angeles at least six feet away from everyone I see. Participating in a group walking meditation, my feet ground to Mother Earth on unsettled Tongva land. Wearing a blue-and-white pinstriped COVID-19 mask, SPF 30 sunscreen, and a black hat, I’m in a sea of hundreds of people. It’s a dry and hot summer day.

I am terrified of dying from COVID-19. It’s a few months into a global pandemic. I’m like a bird flying in a flock. I am nervous about being close to a bunch of strangers, since I have not participated in any group events in nearly three months.

Almost 50,000 people have already died in the United States from the coronavirus. I don’t want to be one of them if I can avoid it. The crowd saunters at a slower pace than a normal walk. I’m at the Great Awakening Walk: Buddhists for Black Lives Matter.

A few weeks earlier, a cop named Derek Chauvin murdered George Floyd, while two other officers looked on. A bystander took a video of the murder, which is the only reason I know about it. Chauvin cut off George’s oxygen supply. In the video, Chauvin kneels on the man’s neck for nine minutes and twenty-nine seconds.

Remediating the Violence in Our Bodies

Hundreds of us walk together from the Japanese American Museum to city hall. I do not identify as Buddhist, yet I meditate and I want to support Black Americans. We are on a slow, methodical, silent marching meditation led by Buddhist monastics. Five men of Asian descent, who wear red robes, lead us down the streets of Los Angeles.

We are in a rhythm like birds migrating south for the winter. Marchers carry signs that say:

End Racism Now!

Black Lives Matter!

Defund the Police

It's an anti-racist, pro-abolition march. Abolition signifies the end of prisons and policing. It means that the state no longer locks people up in cages. We joined the millions of others, marching in solidarity, to end institutional violence against marginalized groups.

A March to End Incarceration

We demand that our society no longer be tied to punishing, dehumanizing, or incarcerating fellow humans. We walked together, collectively grieving for those we have lost to state sanctioned anti-Black violence.

Calling for our government to meet people's basic needs around water, food, shelter, and healthcare. Many people carry posters with photos of unarmed Black people murdered by police, armed security, and law enforcement. I recognize Trayvon Martin, Sandra Bland, and the many images of George Floyd. I feel deeply for these people and their families.

As we walk, our group controls the streets. Traffic stops. Cars give us the right of way as we march toward city hall. I am walking as slow as I can remember; the tone is reflective. I am scared of getting close to people who may have the coronavirus, yet I feel connected to everyone marching with me. I sometimes walk ten feet away from people.

Remediating in the Midst of Chaos

Nearly everyone is wearing a mask, which helps to ease some anxiety. As the group progresses, its meditative pace helps me gain some perspective. I march with this group of strangers, thinking thoughts like:

Black people are getting murdered by police in broad daylight. Their trauma must be raw, deep, and real.

With my white skin, I am privileged that my run-ins with police have often involved traffic tickets, underage drinking, or underage gambling. Minor misdemeanor offenses. I have never been scared for my life.

I have seen a grainy video of Rodney King getting physically assaulted by police. I feel guilty that I didn’t act as a younger person. What was I thinking?

We march to city hall, where stickers saying “Defund” are plastered on the wall. We end up standing together in silence. Monks lead us in silent prayers. Groups of people honor images of George Floyd, Trayvon Martin, and Sandra Bland, taking turns to bow to the larger-than-life images of the recently fallen.

The Force of Collective Grief

Our pain is fresh. We are honoring their lives as though they were saints or deities. But they were people. I’m sure the family of George Floyd wishes that he were still alive and not being honored in spirit. We are collectively mourning. I have never honored people like this before, bowing to the spirits of Tamir Rice, Tanisha Anderson, Michael Brown, and Eric Garner. It hits me that these people are never coming back.

I think about my own role in racism. Random thoughts come over me:

My grandparents have English and German on their side. I don’t know if my ancestors owned slaves.

Growing up in Des Moines, Iowa, my entire street was full of white people.

As a white kid, my parents never gave me “the talk” about how to act when I am inevitably pulled over by police.

I benefited from a racist system my entire life.

People continue taking turns bowing. I am no longer thinking about my risk of getting the coronavirus. Instead, I think:

Why should Black people have to be the only ones risking their lives to march?

Why did it take so long for me to see it? The racism and white supremacy are baked into our Constitution.

The founding framers were white men, and they had dreamt of a more perfect union.

Finally, the last group of those marching with us bows to honor the slain Black people. Sweating through my clothes, I am hot and emotional, ready to return home. I stop by a pizza place by my parking garage and order two greasy cheese slices. This is the first time I’ve eaten out of my home in three months.

Decomposing the Violence in My Own Life

Walking back to the garage, eating the pizza in my car, I think:

What is my role with this?

I went to a predominantly white college. Most of my bosses at work have been white and male. I’ve been a part of white-dominated organizations from childhood until the present. How am I supporting white supremacy? Whether I consciously or unconsciously support this white-supremacy tradition, I am an active participant.

Marching to honor injustices against Black Americans is a choice I made. Yet it does not change that I ignored systemic injustice like these for decades. Denying the reality that we live in a carceral state.

I watched Rodney King’s body get beaten down on grainy camcorder footage while I was in high school. I didn't take any collective action afterwards. It was easier for me to look beyond these societal problems.

Rather than address the root cause of white supremacy, I decided to treat the symptoms. I am not a victim, nor am I a perpetrator. I am an enabler. Is there a healing process for a society built on the foundation of white supremacy? How do we provide accountability and justice for those ravaged by it? What does this even mean? Can we heal?

I don’t have the answers. I honor people like George Floyd more in death than when they are alive. How many people have to die before white people like me do something?

Thanks for reading! See you next time.